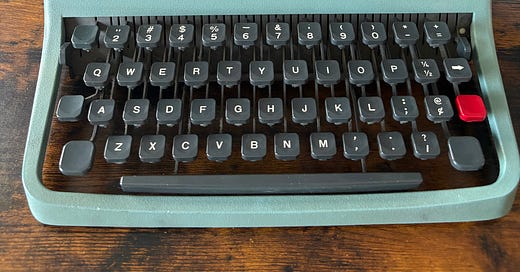

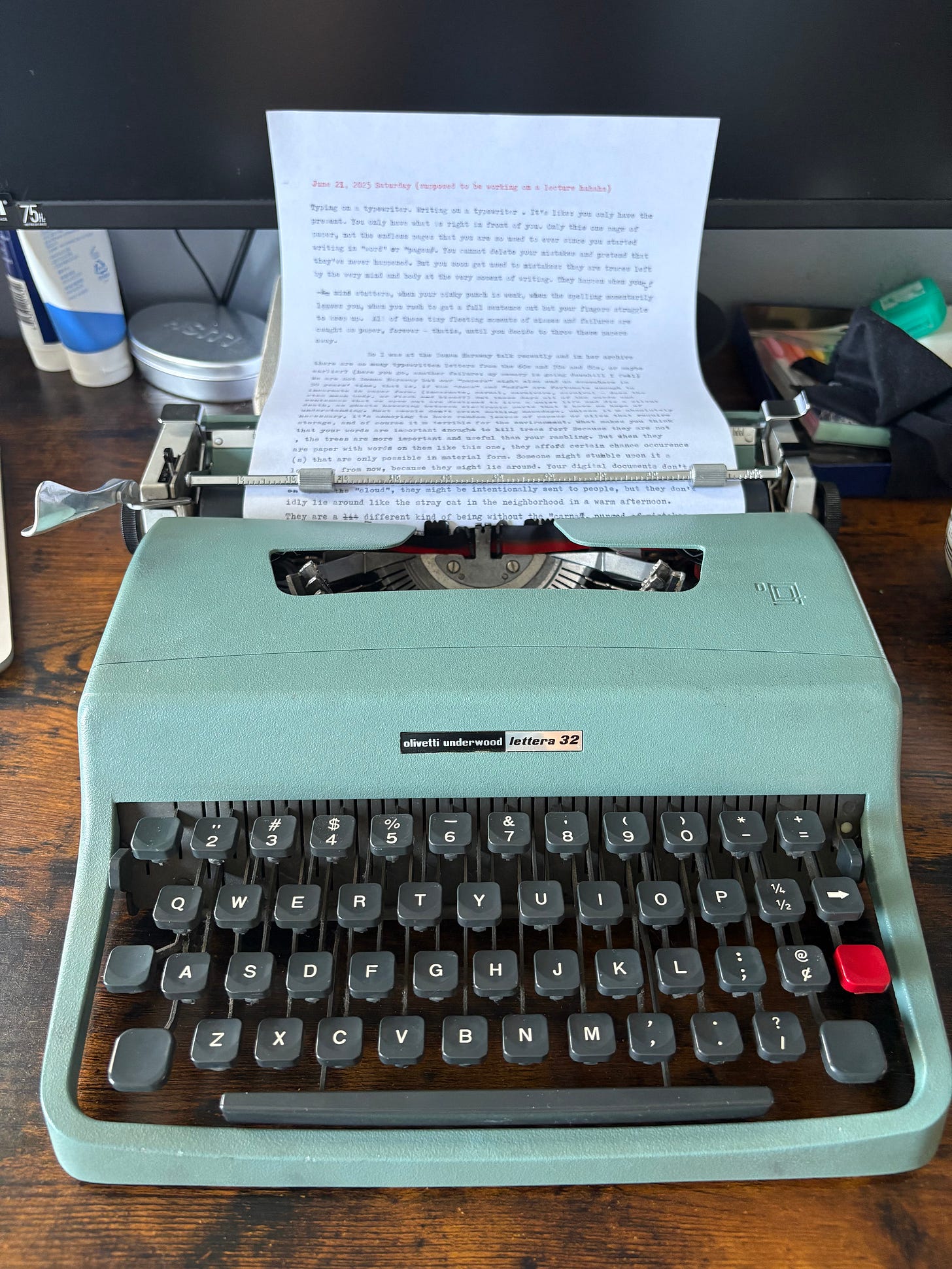

Typing on a typewriter. Writing on a typewriter. It’s like you only have the present, only what is right in front of you, held down by the bail rod of the machine. Only this one page of paper, not the endless pages that you are so accustomed to with “Word” of “Pages”. You cannot delete your mistakes and pretend that they never happened; but you soon get used to mistakes: they are traces left by your mind and body at the very moment of writing. They happen when your mind stutters, when your pinky punches are weak, when your spelling brain momentarily falters, when you rush to get a full sentence out but your fingers struggle to keep up.

All of these tiny fleeting moments of misses and failures are caught on paper, forever — that is, until you decide to discard these loose sheets.

I briefly flipped through Donna Haraway’s archive at our university recently. In her archive, there are so many typewritten letters from four or five or six decades ago. Obviously, we’re not Haraway, and no one cares that much about our papers, but all the same, our “papers” might also end up somewhere in fifty years’ time, if the “docs” and the “pdfs” are fortunate enough to incarnate in paper form. (Incarnate, carnal, carnivore, carnival — the latin word carnis means flesh, or meat, or the body, or fleshly things. Words on paper is the carnis of writing.) But these days all the words and sentences that we spew out are destined to live a quiet life and die a silent death; or more like, they’re born as ghosts that hover between circuit boards and semiconductors and electronic parts that I have no hope of ever understanding. Most people don’t print nothing nowadays: it’s annoying to have random leaves, or piles of paper that require storage, and of course it’s terrible for the environment. What makes you think that your words are important enough to kill trees for? Because they are not; trees are more important and useful than your rambling.

But then, when they are paper with words on them like this one, they afford certain chance occurrences. Someone might stumble upon it a long time from now because it might lie around. Your digital docs don’t lie around; they are stored and safeguarded in your electronic devices, maybe up on the “cloud.” They might be intentionally shared with people, but they don’t idly lie around like the stray cat in the neighborhood on a warm summer afternoon. Digital docs are a different kind of being without a body, or a body without organs, purged of mistakes, neat, clean, correctly formatted — they are everything that an incarnated piece of writing is not, even if they share a certain semblance.